Gwen Spicer graduated from the art conservation program in 1991 and has preserved textiles, historic papers, and upholstery through her Albany-based business, Spicer Art Conservation, for nearly 20 years. Spicer recently took a detour into the world of sound conservation, helping to capture one of the earliest known recordings of a human voice.

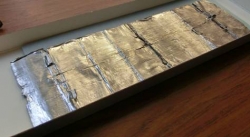

When Thomas Edison’s famous phonograph was demonstrated to an audience during a sales event in 1878, a voice was captured on a piece of tinfoil. The recording was folded and stuffed into an envelope for years until the Museum of Innovation and Science (miSci), then called the Schenectady Museum, discovered the piece in its archives.

When Thomas Edison’s famous phonograph was demonstrated to an audience during a sales event in 1878, a voice was captured on a piece of tinfoil. The recording was folded and stuffed into an envelope for years until the Museum of Innovation and Science (miSci), then called the Schenectady Museum, discovered the piece in its archives.

In 2010, Chris Hunter, miSci curator and director of special collections, approached Spicer to flatten the foil and prepare to send it to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for preservation. At the Berkeley Lab, scientists would try to unlock the sound captured on the foil using state-of-the-art digital technology. The restoration was part of a larger project with the Library of Congress to restore, preserve, and create digital access to old sound recordings using non-invasive optical methods.

“It’s only been recently that this technology has occurred where we can capture sound from these objects,” Spicer said. “We were thrilled to take on such a unique task.”

In the fall of 2012, the voice on the late-nineteenth-century recording was revealed. Thomas Mason, a political writer from the St. Louis Free Republican who bought one of Edison’s machines, can be heard playing a short cornet solo, reading the nursery rhymes Mary Had a Little Lamb and Old Mother Hubbard, and laughing. Listen to the recording.

The purpose of a sound conservation project is to reveal the information an object contains, rather than preserve its aesthetic beauty. In this case, the modern tools art conservators usually employ were ineffective, Spicer said. Instead, she had to use the most rudimentary tools to painstakingly flatten the tinfoil by hand without tearing it.

“I relied on what I learned in the art conservation program,” Spicer said. “I did have knowledge of metals; its properties and how it ages. But tinfoil or even tin as a material does not commonly come up to be conserved. So I was thinking about how to unfold this very fragile textile, even though it was metal.”

Naturally, working with the tinfoil posed a different challenge than she had experienced conserving upholstery, flags, and Civil War reenactment uniforms.

In the end, Spicer’s expertise and attention to detail paid off with the unveiling of the historic recording.

“What I like about art conservation is the problem-solving,” Spicer said.

Some content on this page is saved in PDF format. To view these files, download Adobe Acrobat Reader free.